|

We were told that the management, Derek McEwen and Brian Highly, were

very keen that Civil Aid should help. They were catering for 15,000

to 20,000 people, but if it was a great success, there might be up to

50,000 there. This would put a terrific strain on the organization,

and they would be very glad if Civil Aid could provide field telephone

communications around the site for them, help the St. John and Red Cross

with First Aid if needed, and be prepared to do emergency feeding if

the commercial caterers ran out.

We had got promises

of help from several of the Yorkshire Civil Aid units, and could cope

with the communications and first aid, although they were a bit short

of field cable, but they had no-one who could do emergency feeding,

and could Rochdale help out on this one. Rochdale being in the North

West region, it would be a good opportunity to practice cooperation

between Regions.

The Rochdale Civil

Aid Treasurer, Ernie Flaherty, went over to the next meeting, and agreed

that Rochdale could provide 5,000 portions of soup and bread if the

management would advance the money to purchase it. We only had one Soyer

boiler at the time, and to do 5,000 portions in 24 hours or so, really

needed a second, so he went to Lytham St Annes and bought another.

The cheque for £80

to buy soup powder and bread arrived just in time to get the food before

the festival, and an advance party from Rochdale went over the Krumlin

on Friday. They found that the Huddersfield, Bradford, Leeds and Sheffield

Units were there, and had been spending their evenings all week laying

cable round the site. The portable switchboard was in the stone barn

attached to the farmhouse, north country fashion, at the top of the

site, and this barn was being used as Civil Aid Headquarters, although

the management had provided a small tent, a 10ft marquee down at the

bottom, near the stage, beside the other service tents for Police, First

Aid, Release, Church, and so on.

The very first task

Civil Aid had been asked to perform was to provide telephone communication

between the Police Wireless caravan up the hill in the Car Park, to

the Ambulance Service temporary station in an old mill at the very bottom

of the hill. And what a hill it was. The site was a typical Pennine

hill farm, on steep hillside, with a narrow winding lane coming in at

the top,no proper road down through the fields, only a path that would

be suitable for pack ponies in dry weather. The land was infertile boulder

clay, in an area of high rainfall, where every valley has its reservoir

to feed the neighbouring industrial towns. This valley had just had

a new reservoir built, the Scammonden Dam, that combined the reservoir

with a viaduct for the Lancashire Yorkshire Motorway, M.62 |

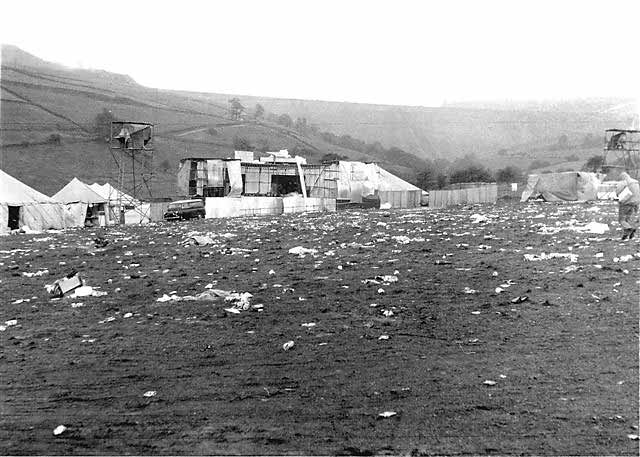

At the bottom of

the farm, at the end of a new road that had, been built on the line

of a former farm track was the scaffolding stage, backed by caravans

for use by the management and as dressing rooms for the groups, and

stretching up the hill towards the farmhouse at the top was the arena

for the fans, who could sit on the hillside in the manner of a Greek

theatre. The perimeter was fenced off with scaffolding and chain link

netting, and around the edges were marquees for selling food and beer

and jewellery, candles, 'underground' magazines, camping equipment.

In a field alongside the arena was the main camping area, already covered

with tents. There seemed to be several thousand there already, and the

staff of stewards and so on were very busy. A11 the staff and management

were following the hippy convention of jeans and tie-dye tee shirts

and long hair.

Given a site on a

hill farm, which proved to have been unwise, the management had planned

very well to meet every contingency. They had a water supply feeding

large tanks they, had bucket latrines in marquees sited close to hard

roads where they could be emptied by the local council tank carts, they

had a good supply of electricity, they had field telephones, they had

a hospital tent with a large staff of volunteers manning it, the ambulance

service were standing by down the hill, there were police from all over

the Ridings of Yorkshire. They did not foresee the terrible weather

that was to hit them, but such weather was exceptional for August, even

in the Pennines. When it came, the services and the voluntary organizations

were just able to prevent loss of life. But there were plenty of inconveniences.

The toilet tents were a long way from the first aid and civil aid tents.

The arrangements for feeding the voluntary staff were most unsatisfactory

they were to buy their own food and claim compensation from Northern

Entertainments afterwards, instead of being supplied with a free meal

pass as had been arranged. The marquee for Civil Aid was already too

small. We were able to remedy some of these faults with the main Civil

Aid party that arrived on Saturday.

The site on Sunday |

Civil Aid split into

three shifts so that we could give continuous coverage, manning the

switchboard and so on, Duty shift, stand-by shift and off-duty shift,

who would only be called in an emergency, each shift lasting four hours.

We found that the

field telephones could only be operated effectively if we placed a Civil

Aid member at each as operator—if we did not, either there was

no one there when a call was made, or someone would pick up the phone

but not realise that it operated on a pressed switch and so could not

make himself heard. As a result of this policy of supplying operators

we were able to keep effective communications throughout the duration

of the festival, but it strained our resources of manpower, and during

the night we withdrew most of our operators.

During Saturday afternoon

a crisis of management developed. This was mainly due to inadequate

financial arrangements. As much of the ticket money was held by ticket

agencies, there was not enough ready cash to meet all the needs. A couple

of cheques bounced, and the Groups lost confidence in the managements

ability to pay them, and one or two insisted that they would only appear

if they were paid cash, and there was not enough cash. There were delays

and arguments. One of the two organizers of Northern Entertainments

disappeared, last seen walking over the moors in a daze, the other collapsed

under the strain, and was out of action for several crucial hours.

But as so often happens

during a time of crisis, fresh leaders emerged, and these formed themselves

into a new management. They were Huw Price, the site foreman, John Gawkroger

who had come in at the last moment to oversee the ticket sellers, Brian

Wickham, who had the beer tent concession, and4, Les Allen, an agent

from London, who knew all the groups. Between them, informally, they

decided that the show must go on for the sake of the thousands of kids

who were now there, having travelled from all over Europe, Africa, America,

as well, as England, Scotland and Wales. Brian advanced money from his

bar takings to meet certain immediate expenses, John used the money

from the gate to pay the Groups travelling expenses:: and hotel bills,

Huw paid the stewards enough to be able to eat (some of this coming

from the sale of programmes in the arena by Civil Aid members who were

aware of the situation and were doing what they could to help so that

the show could go on,) Les contacted Groups managers by telephone, including

those still in London, and persuaded them to appear for expenses only

on the following day. Ginger Baker in fact turned up on the Sunday to

play free of charge, not even asking for his expenses , but by that

time the festival had been abandoned.

This new management

tackled the whole situation and solved every problem as it arose; problems

were continuous, varying in size from peanuts to mountains. By dark,

confidence had been restored among the groups and the staff, and the

future of the festival was assured- it was expected to at least break

even as a result of Sunday ticket sales, with the faint possibility

of a large profit. One of the major problems had been forged tickets

that had been spotted at the gates—the gang involved in the forgery

were located and checked, but this had a disastrous effect on ticket

receipts.

At about midnight

the Groups stopped playing for the night there had been some heavy showers

and there was a rash of short circuits on the stage, where the loudspeaker

system had an output of about 2,000 watts. A discotheque continued in

a huge inflatable tent near to the Civil Aid tent. |

I had gone off duty

at 10 pm and climbed into a sleeping bag in a tent belonging to Ernie,

our Treasurer . I had been vaguely aware that the Groups had stopped

playing, and although half asleep at the time, heard the Discotheque

stop and then the huge electric fan that kept the tent inflatable stopped

too. Soon after, as the tent deflated, it could be heard flapping in

the wind, which was rising, and presently there was very loud crack,

like a whip crack, as the dome was caught by the wind and then collapsed

. I had heard rain on the side of the tent, and had wondered about the

campers, many of whom had only a plastic bag that they had climbed into

in the arena, or nothing at all for shelter.

We were woken by

the Duty shift at quarter to two and warned that the weather was getting

worse. As we came on duty, the arena was beginning to clear, and campers,

already very wet were looking for shelter pushing into the marquees

or standing on the lee side out of the driving rain. The rain started

to get really heavy, and the flow of campers looking for shelter increased.

Ernie, who was shift leader, decided that the soup might be needed,

and got the Soyer boiler going. The only fuel that could be found to

light it in the wet and dark was the poles of the collapsed marquees

(one had gone down already), so they were chopped up, and the fire lit,

the water brought to the boil' the soup powder lit. While this was being

done I went round the whole site, checking on what food was available.

There were only four hot-dog stalls and a milk bar, none cheap.

I checked with St

John and Release, both of whom we had already found most co-operative,

and found that they were beginning to get worried about cases of exposure.

So Civil Aid said 'Right. Free soup for all who need it. Keep them warm.'

As soon as the first 5 or 6 gallons was ready we carried it to the Release

and First Aid tents in jugs, and as we did this, the situation got worse

and worse, more and more campers crowding into every space they could

find. The First Aid parties started to find cases of serious exposure,

people so cold that they could not even lift a plastic cup to their

mouths, cases who had to be carried to the marquee on a stretcher. The

ground became mud, everyone was slipping and sliding on the steep hill,

tents started to blow down, plastic sleeping bags were caught in the

gale and wrenched across the ground, scores of people were huddled in

the mud in the lee of the marquees. Civil Aid members were carrying

soup round in anything they could find, dixies, plastic jars - we even

emptied beer and cider out of the plastic gallon jars to carry soup

instead.

At about 4 a.m. there

were two ad hoc conferences in progress, one between the County Ambulance

Officer in charge of the temporary Ambulance station below and the St.

John personnel, who were trying to predict which way the emergency was

likely to develop. The other was between St. John, Release and Civil

Aid, to try to organize additional shelter. The only practical solution

was the beer marquees, but these were closed and guarded by employees

who, quite rightly, would not allow

stray campers in. So George Graham, of Release, got one of the Release

doctors and to go to the Police and persuade them that these marquees

must be requisitioned to prevent loss of life. There were by now very

large numbers of exposure cases being brought in to be treated, many

had already gone to hospital by ambulance.

It was not easy to

get a decision to requisition from the Police. It is a built-in feature

of the Police Force that they do not make independent decisions—they

always consult higher authority, unless it is in the book. Only a Chief

Constable will readily act on his own initiative. Disaster conditions,

although part of the police task, are met with so infrequently that

they are outside their normal experience.

However, by insistence,

the Release doctor managed to get through to the senior Police Officer

on duty, and he authorized the sergeant present to open the beer tents.

Once the decision had been taken, it was very simple. The sergeant simply

demanded to be let in and said ‘We propose to requisition this

tent , will you co-operate?' He got immediate co-operation, and in turn

agreed to leave a constable to prevent any looting. Civil Aid was also

to leave a member to help the campers, and at first only real exposure

cases were let in. But very soon everyone who was out in the open became

an exposure case, and anyone needing shelter could go in. This very

large, in fact double' marquee just succeeded in taking the people still

left outside. There was not one single case of anyone trying to take

a free drink. The behaviour of the 15,0004 campers was of the highest

order, with two exceptions.

The first of these

was an attempt to extort money from traders by threats, at about dusk

on Saturday night. The second was the three or four drug cases arrested

(although rumours were circulating that over one hundred had been 'busted'

by the ~ police—but this was rather indicative of the ill feeling

that existed for the police). In one of these cases the man arrested

was very roughly handled by the police—he was 'high'. There was

a very strong protest by Release' one of whom had witnessed the arrest.

Police behaviour after that was perfect , but it did not help the feeling

of resentment the two philosophies of hippy and police being to an extent

incompatible. It would have done a great deal to improve relations permanently

if police had physically helped to carry and distribute soup, so that

they could have been seen to be concerned with the welfare of the campers.

Many people were seen to help, but they were anonymous. One helper in

particular must be singled out -a male nurse from Lancashire who worked

throughout the night with the Civil Aid volunteers. At the time I thought

he was a member of one of the Yorkshire Units of Civil Aid.

Shortly before dawn

the pressure had become so great that all the off-duty shift of Civil

Aid had been called out, and it was soon after this that the gale returned

with renewed violence and marquees and tents collapsed, including the

beer tent crowded with campers, watched over by a member of Civil Aid.

Huw Price was at this time trying to get riggers in to reinforce the

guys of the marquees, but this was not easy on a Sunday morning, and

they did not arrive in time to save the tents. With the dawn the problem

started to ease, as people came to life in their plastic bags and started

to move about and warm up. The number of fresh exposure cases slackened

off and some people started to climb the hill to leave the site.

At about 6 a.m. there

was a quick meeting of the new management to discuss the situation and

see if it would be possible to continue. At that time the word was passed

round that it was intended to continue with the day's programme, if

later circumstances would permit. By now there were queues of people

forming at the Soyer boiler beside the Civil Aid tent,and the second

boiler that had been operating up at the farm was brought down to the

centre of the site. At about 7 a.m. Ernie collapsed from the strain

he had been working under. A doctor from Release quickly got him away

to hospital, with his daughter Lesley, who had gone off duty after the

beer tent had collapsed over her head. |

|

At a little before

8 a.m., the management all got together at the farm, went to see the

Police, decided that the stage was no longer safe, that the show could

not possibly go on, so the festival was called off. Although at this

time the weather was looking better and there was a good forecast, it

was a wise decision, because the wind rose again, most of the remaining

tents collapsed, there were frequent heavy showers, and a retaining

wall in the farmyard collapsed.

Campers were streaming

off the ground, and the Police got in touch with the Bus Company to

get the special evening service brought forward to deal with them. The

medical and First Aid teams were still under heavy pressure and the

ambulances were kept busy until mid afternoon moving hospital cases

that were carried over the mud in mountain rescue sledges. Teams from

Bradford, Leeds and Huddersfield Civil Aid came in and took over from

those who had been on duty all night, who managed to get a snack and

a few hours rest. By early afternoon there was no real problem left

to deal with and the Civil Aid party went home, returning during the

week to reel in field cable lines.

70 extreme exposure

cases had been sent to hospital, and 330 treated in the First Aid tent.

It took me about two days to recover physically from Krumlin, and then

another three to get some of the loose ends sorted out, especially the

financial ones. We were about £200 down overall, including nearly

£150 for the Rochdale Unit, whose cheque for the purchase of soup,

cups and bread had bounced.

Contact

us if you can help.

Back

to the main Archive

|